Neuroscience & Law

What do emerging questions of the capacity for agency, bias, and identity in the human brain mean for the balance of America’s justice system?

Neuroscience & Law

What do emerging questions of the capacity for agency, bias, and identity in the human brain mean for the balance of America’s justice system?

FREE WILL

How can we interpret the scientific findings that contradict it?

Robert Sapolsky: Questions About Free Will That Undermine the Prison System as We Know it

Read the full Brein in Actie article for more info

In a study by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s, participants were told to press a button at any moment of their choosing, and note the precise timing they were aware of their decision (to the millisecond) on a clock next to them. While doing this task, the participants were hooked up to EEG (electroencephalogram) equipment which could read the electrical activity of their brain, and therefore assess when their neural networks actually made the decision to move and press the button. Libet found that the “readiness potential", electrical activity signifying the activation of neural connections, occurred about 300-500 milliseconds before most people claimed to be conscious of their decision. There are a variety of ways to interpret this evidence: Many claim that this study completely disproves free will by demonstrating the subconscious nature of decisions, while many claim the timing could have been off, or that we still have the ability to “veto” these subconscious decisions up to the last moment.

The court already acknowledges the ambiguity of free will and the potential of diminished responsibility, like these examples:

George Zimmerman

Zimmerman was found not guilty after killing Trayvon Martin by reason of self defense. The jury controversially believed he truly had no choice in his actions.

John Hinckley Jr.

After Hinckley’s assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan, he was sent to a psychiatric institution as opposed to jail, by reason of the insanity defense; the jury believed he did understand his actions in the moment, and was therefore not responsible for them.

Miller v Alabama/

Jackson v Hobbs

Children and teenagers are unable to act as responsibly as adults, and therefore don’t hold the same amount of responsibility; in 2012, the Supreme Court made a joint ruling to ban life without parole for juveniles.

Sapolsky’s scientific reasoning is research-backed and difficult to refute. However, there are a many interpretations on varying levels of extremity:

Consider…

The Insanity Defense

How does the system react to people diagnosed with an inability to reason?

Why is it so contentious? Here is one example.

How far could the insanity defense extend?

The temporary insanity defense is sometimes not distinguished from the regular insanity defense. However, there are some cases where the court cannot prove the defendant has impaired judgment on a regular basis, and did only at the time of the crime. For example, state laws differ on whether they consider voluntary intoxication a viable use of the temporary insanity defense. Temporary insanity is often associated with “crimes of passion”; in 1859 U.S. Congressman Daniel Sickles shot and killed Philip Barton Key after finding out he was having an affair with his wife, and was acquitted (the first official use of the temporary insanity defense in the United States).

For neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, new technologies, mainly Deep Brain Stimulators (DBS) are emerging with the potential to drastically reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. For Parkinson’s, DBS targets the subthalamic nucleus (STN) to reduce tremmors. The STN is crucial to motor-control, but also cognition and emotion (specifically reward and decision-making circuits).

Parkinson’s disease is linked to low levels of dopamine, which is often replaced through medication. Dopamine replacement medications can disrupt reward circuits and lead to impulse control disorders, which produce behaviors like gambling addictions, hypersexuality, and inappropriate/uninhibited social behavior. In some cases, DBS is thought to replace dopamine therapies and therefore alleviate problems with impulse control. Stimulating the dorsal STN, which is linked to motor control, does not seem to produce any separate issues. However, stimulating the ventral STN, which is linked to emotional processing, can lead to decreased impulse control.

While it seems possible to mitigate this risk by adjusting the voltage and target area of the DBS treatment, patients still have to assume risk of behavioral changes, some of which can be linked to violence and crime due to lack of inhibition. This risk comes both through the known treatment of dopamine replacement therapy, and the novel treatment of DBS. Balancing the need for medical treatment with the risk of harmful behavior is ethically very difficult, and could be another example of diminished agency in criminal activity.

Read this Nature study on different areas of the STN and how they can distinctly impact behavior

Consider…

The Impulse Problem

Damage and underdevelopment in brain regions like the prefrontal cortex can tremendously impact behavior. What does this mean for responsibility?

The Prefrontal Cortex: A Natural Crime Shield

Underdevelopment, brain damage: Enough to Acquit?

Take a look at these cases to see where impulse came into play.

Sentencing age peaks at 23. Accounting for trial time, the estimated peak age of offense is 22.

Evan Miller was sentenced to life without parole at the age of 14 after brutally murdering his neighbor. In 2012, the Miller v Alabama supreme court case ruled that LWOP for juveniles is unconstitutional, since children have a “diminished culpability and heightened capacity for change.”

In his re-sentencing hearing, the judge was urged to consider other circumstances from Miller’s past as well, including a history of attempted suicide, foster care, and severe abuse, as well as whether he had shown signs of reform in his first 14 years of incarceration.

Miller’s case has faced much public controversy; the extreme nature of the crime, coupled with his turbulent past and youth, leave people morally baffled.

There have been many cases of youth LWOP in cases far less severe than Evan Miller’s.

2 in 5 given life without parole were under 26 at the time of their sentence (based on a newly compiled nationally representative dataset of nearly 30,000 individuals sentenced to life without parole (LWOP) between 1995 and 2017.)

In the case of Donta Page, convicted of the brutal murder of Peyton Tuthill, evidence of his PFC damage was enough to change his death sentence into LWOP. Everyone, including judges, the victim’s family, and the public, was conflicted over this decision, ultimately deciding Page’s specific circumstances (including severe abuse and brain damage) were enough to push his crime below the level of extremity required for death row.

Washington Post “Donta Page: Can Brain Scans Explain Crime?”

Consider…

BIAS

With the seemingly unavoidable presence of implicit bias, how do we adjust behavior to approach justice in the criminal-legal system?

Assess your bias by taking an Implicit Association Test

Read more from MIT on the brain mechanisms of bias, and how to control it

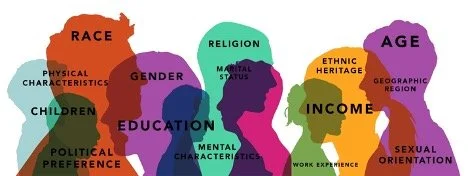

The Harvard Implicit Association test offers a simple way for people to assess their racial bias, as well as many other categories including religion, gender, and sexuality.

Responsibility for IAT is controversial. The immediate response itself seems to be out of one’s control, but how you respond to bias can be consciously decided in the moment. Mitigating bias requires an awareness that it exists in the first place.

A test that associates race with recognizing an object as a gun vs a neutral object reveals bias in this area, which contributes to the prevalence of police shootings of Black Americans. Similar racial biases can impact juries and judges in how they evaluate defendants.

Most test-takers are implicitly biased towards European-Americans.

Most test-takers associate Black with weapons and white with neutral objects. This is thought to lead to wrongful assumptions that Black people are carrying weapons.

Consider…

TRAGIC ERROR

False accusations upend lives. How can neuroscience shed light on the mechanisms of these tragic slip-ups?

How Do False Confessions Come About?

Read more about “The Psychology of False Confessions” from Psychology Today

Read more about “How Should We Interrogate The Brain and the Impacts of High Pressure”

“Stressors, depending on their severity, chronicity and type, usually impair encoding of memories, disrupt consolidation of memory, and erode retrieval of memories (even of simple, straightforward, declarative and fact-based information).” - Shana O’Mara, D.Phil

One of the most famous cases of false confessions: The Central Park Five. In the 1980s, five black and brown teenage boys were arrested for the rape and murder of a white jogger in Central Park. They were coerced into confessing by the police’s interrogation techniques, thinking they had no other option. All of them spent at least six years in prison, until they were exonerated following the confession of Matias Reyes (an already convicted murderer and rapist).

This case derailed five young people’s lives as the world looked on, all because of police manipulation in place of clear evidence.

The exoneration ended in a 41 million dollar settlement. The state of New York denied any fault in the error.

New York Times: “The Central Park Five: ‘We Were Just Baby Boys’”

Recommended viewing: “The Central Park Five”, (2012 Documentary) and “When They See Us” (Netflix series depiction)

Barbiturates, substances that target the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), put humans in a state of partial consciousness and can be used to treat epilepsy, anxiety, pain, and sleep problems. They increase the presence of GABA, the neurotransmitter that slows down brain activity. However, since barbiturates supposedly lower inhibitions by damaging focus enough to prevent lying, in some cases they have been coined “truth serums” and used in interrogation practices. This was done during the cold war by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), to catch double agents working for the Soviet Union. Most recently, the use of “truth serum” was approved by a judge to be used on James Holmes, who was on trial for a mass shooting and claimed the insanity defense. The judge’s goal was to see whether Holmes actually had impaired judgment at the time of the crime. Although the serum was never used in this trial, the potential use of it shocked many experts who worry that the drug would not encourage accurate statements (and might diminish memory accuracy altogether).

In 1989, Ada JoAnn Taylor was part of a shocking series of false confessions to the sexual assault and murder of 68-year-old Helen Wilson. She had been sexually assaulted in the past, and following coercive interrogation techniques she began to remember being present at the assault. It became clear she was confusing memories of her own traumatic past with this event; when questioned she remembered Wilson’s assault taking place at a house similar to her childhood home, but when presented with evidence that it was in an apartment building, she adjusted her memory.

The five other people convicted came from similar backgrounds to Taylor: they grew up in small white towns where police officers were like “guardians,” and most came from severely broken homes. Only a couple came to doubt their involvement after several years of imprisonment, prompting a DNA test that ended up exonerating all six of them. Even after exoneration, Taylor experienced false flashbacks of the event.

This case shows the malleability of memory, and once again the danger of coercive interrogation. The six accused people were evaluated by psychologist Wayne Price, who encouraged them to dig deep and find hidden memories. His methods likely contributed to the false memories, and provides a cautionary tale for blind trust in any sole “scientific expert” involved in criminal proceedings.

Consider…

NEUROIMAGING

Can emerging neuroscience capabilities help provide objective evidence?

Vincent Gigante started acting strange. He would walk down the streets in pajamas muttering to himself. How could this be the high profile crime lord everyone knew? Suspicions arose that he was putting on an act to be able to claim the insanity defense. Several experts testified on his behalf, claiming he could not be tried due to psychosis. There was also a possibility of dementia, which the defense tried to support with PET scans.

Jonathan Brodie, psychiatrist and technical advisor to the judge, argued the PET data was inconclusive. Gigante was found guilty and confessed to faking mental illness, and later evidence suggested that he was indeed quite mentally competent; it was all in the interpretation of data.

Prediction of criminal behavior, while not exceedingly common, has been around formally for several decades. One of the first clear cases was Thomas Barefoot, who was convicted of killing a police officer. Following testimonies from psychiatrists that labeled Barefoot a “criminal psychopath,” he was sentenced to death, largely due to fears of what he would do in the future. Risk assessments have been carried out since then using a holistic range of factors, but often end problematically entangled with bias.

Some neuroscientists claim the field could enhance risk assessments and make them more objective. This is quite a controversial topic, reminding people of eugenics and pseudoscience practices that were commonplace not too long ago.

Consider…